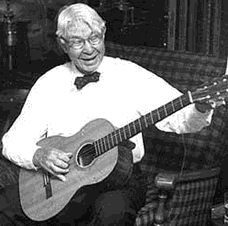

Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900-2002)

Now I have just come across an article by Richard Palmer, Gadamer's foremost American interpreter, that confirms my intuitions. Below is an excerpt from Palmer's article, "Gadamer’s Hermeneutical Openness

As a Form of Tolerance".

Gadamer’s contribution to moving toward a just society

Gadamer, we must say in advance, does not come forward with a program or concept of justice. Yet the hermeneutical philosophy of Gadamer does have something to offer, because in fact something more than tolerance is needed—something more than enduring the presence of the Other, or putting up with oppressed people who are asking for their rights, or even asking for reparations—if we are to move forward together in justice and peace. We need to understand the Other. What we need also are international rules of fairness and justice for all, not powerful states pursuing only their own economic gain through a process they call “globalization.” What is needed is a new sense of justice and respect and fairness in international trade. But where Gadamer can help us is with some principles of dialogue and a sense of what is involves in the processes of understanding and also what Gadamer calls Verständigung—reaching agreement in understanding.

A. Some Principles of Dialogue

I would like first to describe a six elements of this modest yet important

hermeneutical factor in moving forward toward agreement in understanding, and then, in a subsequent section, to examine Gadamer’s project of restoring respect [this is related to tolerance] to the humanities and fine arts.

1. eumeneis elenchoi. In entering a dialogue, one should follow the Socratic principle of good will, of eumeneis elenchoi—the other person could be right! In a genuine dialogue, like a dialogue with Socrates, one is not seeking to win an argument or to score points but to understand the other person’s viewpoint and to work out a mutually satisfactory agreement in understanding. This requires a hermeneutical openness to the other person’s viewpoint and his claims, not just openness to an ancient text and its claim. You could have something to learn from

the other person. At the end of a conversation I recently edited, Gadamer

unexpectedly replied to a classicist professor who understood him to be saying we really must go back to the ancient Greeks to find wisdom today, saying: “Yes, but perhaps we have something to learn from the East….”16 Here he is showing respect for another tradition with another history, suggesting that he could have something to learn from another culture. And this same respect we must accord a person from another tradition. This is hermeneutical openness and humility.

I am tempted to say this represents Gadamer’s most important contribution:

We must enter a dialogue with a genuine sense that the other person could be right!

This means: with an open mind. What would our problems today be like, if we entered discussions with a sense that the other person could be right? What would it be like if we entered the discussion not in order to score points in a debate, or show where the other person is wrong, but to work toward a win-win situation where both sides benefit from the agreement that is attained through negotiation.

2. Common ground. It is important to look for common ground, for things you both agree on, things you both are seeking. First carve out areas of agreement and commonality before trying to deal with your disagreements. Be willing to learn from your disagreements! This is a basic principle of dialogue.

3. Respect. Above all, treat your dialogue partner with respect. You should not demonize or dehumanize your partner or seek to undermine his or her standing or claim. No. Demonizing is a strategy of military thinking in order to justify violence and murder of the other person....

4. Tolerance. Understand the difference between intolerance, which

attacks the partner, and tolerance, which accepts differences in the partner, and which gives the partner the right to be different. Respect and appreciation of the person are lubricants of a good discussion. A dialogue is not a debate you are trying to win but a mutual effort to reach an agreement in understanding.

5. Preunderstanding and “prejudice.” One needs to understand the

difference between prejudice which belittles and discredits the “enemy” in

advance, and the term preunderstanding, a term Gadamer uses in reference to the required knowledge one needs to understand and deal with a problem. Gadamer is famous for his controversial assertion that “prejudices can be fruitful.” He could have saved himself a lot of trouble if he had simply called them by the Heideggerian word, Vorverständnis, preunderstanding, instead of the usual word for prejudice in German, Vorurteil, prejudgments. What he really meant is preunderstandings. With this doctrine he is pointing out that each side brings different prior knowledge, perspectives, goals, understandings, to a discussion—a

different horizon. This occurs when one understands anything: a situation, a text, an issue, a person. A fruitful encounter brings what Gadamer calls “a fusion of horizons.” In a successful dialogue, prior understandings (Vorverständnisse) of facts, of situations, of intentions, of persons, are transformed. Again, a fruitful dialogue need not be only with the tradition and traditional texts—although this can happen—it can also be here and now with a living partner with whom you want to reach an agreement about a situation, issue, text, or the intentions of a

person. A successful dialogue brings a transformation in understanding—of oneself and of the topic.

6. Tradition and Authority. This is a difficult topic in Gadamer. He has been attacked as an unquestioning defender of tradition and authority. This is not true, because for him a dialogue with tradition involves an active use of reason to find answers to questions. It is not an unquestioning acceptance. Sometimes the answers can come from a forgotten aspect of an older tradition, because the tradition is a rich resource.

As regards respect for authority, Gadamer does not have in mind what we

call “arguing from authority” but rather recognizing the fact that authority is not always illegitimate, as certain advocates of violent revolution maintained, in the French revolution, or in the Enlightenment, or later. To prove his point, Gadamer mentions examples of legitimate authority, such as the authority of one’s teacher, one’s superior, or the expert in a field of knowledge. In these cases, one recognizes that the person “in authority” knows more and should be respected, although one is still free to question this authority with reason. But one does not

start with the presupposition that authority or tradition is simply wrong or illegitimate. Gadamer notes that we accept the authority of a doctor because we recognize that he knows more than we do. This is not a blind trust or obedience to authority but a rational recognition that it pays to follow advice and direction of someone with more knowledge than oneself.

Both Catholic and Protestant theologians found in Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics the more moderate attitude toward tradition, authority, and the texts of tradition, in contrast to the Enlightenment and 19th century scientific attitude often of categorical and intolerant rejection of tradition, authority, and the claims of religious texts on the basis of the absolute authority of science. So spelling out the conditions for dialogical openness may be a contribution Gadamer can make to

tolerance and justice.

Gadamer and Palmer