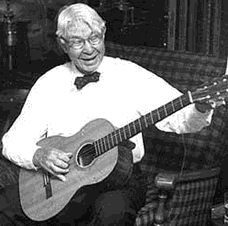

Carl Sandburg (1878-1967)

READY TO KILL

TEN minutes now I have been looking at this.

I have gone by here before and wondered about it.

This is a bronze memorial of a famous general

Riding horseback with a flag and a sword and a revolver

on him.

I want to smash the whole thing into a pile of junk to be

hauled away to the scrap yard.

I put it straight to you,

After the farmer, the miner, the shop man, the factory

hand, the fireman and the teamster,

Have all been remembered with bronze memorials,

Shaping them on the job of getting all of us

Something to eat and something to wear,

When they stack a few silhouettes

Against the sky

Here in the park,

And show the real huskies that are doing the work of

the world, and feeding people instead of butchering them,

Then maybe I will stand here

And look easy at this general of the army holding a flag

in the air,

And riding like hell on horseback

Ready to kill anybody that gets in his way,

Ready to run the red blood and slush the bowels of men

all over the sweet new grass of the prairie.----------------------------------------------

In a letter to Amy Lowell, on 10 June 1917, he wrote:

I admit there is some animus of violence in Chicago Poems but the aim was rather the presentation of motives and character than the furtherance of I.W.W. theories. Of course, I honestly prefer the theories of the I.W.W. to those of its opponents and some of my honest preferences may have crept into the book, as you suggest, but the aim was to sing, blab, chortle, yodel, like the people, and people in the sense of human beings subtracted from formal doctrines.

GOVERNMENT

THE Government--I heard about the Government and

I went out to find it. I said I would look closely at

it when I saw it.

Then I saw a policeman dragging a drunken man to

the callaboose. It was the Government in action.

I saw a ward alderman slip into an office one morning

and talk with a judge. Later in the day the judge

dismissed a case against a pickpocket who was a

live ward worker for the alderman. Again I saw

this was the Government, doing things.

I saw militiamen level their rifles at a crowd of

workingmen who were trying to get other workingmen

to stay away from a shop where there was a strike

on. Government in action.Everywhere I saw that Government is a thing made of

men, that Government has blood and bones, it is

many mouths whispering into many ears, sending

telegrams, aiming rifles, writing orders, saying

"yes" and "no."Government dies as the men who form it die and are laid

away in their graves and the new Government that

comes after is human, made of heartbeats of blood,

ambitions, lusts, and money running through it all,

money paid and money taken, and money covered

up and spoken of with hushed voices.

A Government is just as secret and mysterious and sensitive

as any human sinner carrying a load of germs,

traditions and corpuscles handed down from

fathers and mothers away back.-------------------------------------------------------

All in all, Sandburg was ambiguous about war. Sometimes he supported the First World War (see THE FOUR BROTHERS), and in other writings he opposed it. Sometimes he seems to be resigned to its inevitability. Still, his work warrants ranking him among America's greatest poets.

--------------------------------

FIGHT

RED drips from my chin where I have been eating.

Not all the blood, nowhere near all, is wiped off my mouth.Clots of red mess my hair

And the tiger, the buffalo, know how.I was a killer.

Yes, I am a killer.I come from killing.

I go to more.

I drive red joy ahead of me from killing.

Red gluts and red hungers run in the smears and juices

of my inside bones:

The child cries for a suck mother and I cry for war.------------------------------

WARS

IN the old wars drum of hoofs and the beat of shod feet.

In the new wars hum of motors and the tread of rubber tires.

In the wars to come silent wheels and whirr of rods not

yet dreamed out in the heads of men.In the old wars clutches of short swords and jabs into

faces with spears.

In the new wars long range guns and smashed walls, guns

running a spit of metal and men falling in tens and

twenties.

In the wars to come new silent deaths, new silent hurlers

not yet dreamed out in the heads of men.In the old wars kings quarreling and thousands of men

following.

In the new wars kings quarreling and millions of men

following.

In the wars to come kings kicked under the dust and

millions of men following great causes not yet

dreamed out in the heads of men.---------------------------------

BUTTONS

I HAVE been watching the war map slammed up for

advertising in front of the newspaper office.

Buttons--red and yellow buttons--blue and black buttons--

are shoved back and forth across the map.A laughing young man, sunny with freckles,

Climbs a ladder, yells a joke to somebody in the crowd,

And then fixes a yellow button one inch west

And follows the yellow button with a black button one

inch west.(Ten thousand men and boys twist on their bodies in

a red soak along a river edge,

Gasping of wounds, calling for water, some rattling

death in their throats.)

Who would guess what it cost to move two buttons one

inch on the war map here in front of the newspaper

office where the freckle-faced young man is laughing

to us?--------------------------------

Sandburg held left-wing political opinions and was district organizer of the Socialist Party and in 1910 became secretary to the socialist mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He also contributed poems and articles to The Masses, a socialist journal edited by Floyd Dell and Max Eastman.

------------------------------------------------

Planked Whitefish

by

Carl Sandburg

("I'm agoing to live anyhow until I die."-Modem Ragtime Song)

Over an order of planked whitefish at a downtown club,

Horace Wild, the demon driver who hurled the first aeroplane

that ever crossed the air over Chicago,

Told Charley Cutler, the famous rassler who never touches

booze,

And Carl Sandburg, the distinguished poet now out of jail,

He saw near Ypres a Canadian soldier fastened on a barn door

with bayonets pinning the hands and feet

And the arms and ankles arranged like Jesus at Golgotha 2,000

years before

Only in northern France he saw

The genital organ of the victim amputated and placed between

the lips of the dead man's mouth,

And Horace Wild, eating whitefish, looked us straight in the

eyes,

And piled up circumstantial detail of what he saw one night

running a truck pulling ambulances out of the mud near

Ypres in November, 1915:

A box car next to a field hospital operating room. . . filled

with sawed-off arms and legs. . .

Faces in the gray and the dark on the mud flats, white faces

gibbering and loose convulsive arms making useless gestures,

And Horace Wild, the demon driver who loves fighting and can

whip his weight in wildcats,

Pointed at a blue button in the lapel of his coat, "P-e-a-c-e"

spelled in white letters, and he blurted:

"I don't care who the hell calls me a pacifist. 1 don't care who

the hell calls me yellow; 1 say war is the game of a lot of

God-damned fools."------------------------------

Jeff Sychterz

"Over an order of planked whitefish" Horace Wild relates a series of horrifying images to his friends to explain why, after voluntarily serving in France during in 1915, he now advocates peace. The detached third person narrative of Sandburg’s semi-autobiographical poem avoids rhetoric or editorializing, focusing instead on four short, stark, and largely unadorned, images. Very different from other contemporary anti-war expressions, such as "I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier," the poem can hardly be called an anti-war manifesto. However, after the poem assaults us with those four images, we understand why Wild states, "‘I don’t care who the hell calls me a pacifist. I don’t care who the hell calls me yellow. I say war is the game of a lot of God-damned fools.’" Wild tells his friends—and the poem tells us—that because of those violent "circumstantial details" of war he wears his "blue (Peace) button in the lapel of his coat."

We might say that the horrific images themselves are enough to convince anyone to be anti-war; but representations of war’s violence can cut both ways, by either encouraging people to avoid war, or to enlist. The first two images, for example, resemble alleged atrocities committed by the Germans in their occupation of Belgium, as documented in the Bryce Committee’s "Report on Alleged German Outrages": "at Haecht several children had been murdered, one of two or three years old was found nailed to the door of a farmhouse by its hand and feet . . ." (Bryce Report, Aerschot and District. Period III. [September.]) and "At Elewyt a man’s naked body was tied up to a ring in the wall in the backyard of a house. He was dead, and his corpse was mutilated in a manner too horrible to record" (Bryce Report, Aerschot and District. Period II. [August 25th.]). Some isolationist groups saw the Bryce report as propaganda designed to incite Americans against the German "Huns" and bring the U.S. into the war on the side of the Triple Entente. Whether or not the accusation is true, the Bryce Report, as well as other representations of German barbarity and cruelty, did help to sway the isolationist nation to a position of ideological support for England and France. Representations of violence, therefore, can be used to promote either war or peace.

Sandburg, however, mitigates the pro-war possibilities of his poem through passive constructions, which focus attention on the victims and leave the perpetrators unnamed. In addition, the victims are all soldiers instead of innocent civilians (although the poem does not specifically describe the castration victim as a soldier it also does not name him as a civilian, and in context with the other represented victims the reader is left with the impression that he is a soldier). The poem, therefore, represents the soldiers not as victims of a specific enemy, but as victims of war itself. War, not the Kaiser, is the enemy.

This anti-war message is relayed to the reader through an extradiegetic narrator, but the message is authenticated by the words of an eyewitness to those events, Horace Wild. In the poem Wild is represented as a volunteer corpsman or ambulance driver, "running a truck puling ambulances out of the mud near Ypres in November, 1915," despite the fact that he volunteered as a pilot in the war. The poem’s representation of Wild as an ambulance driver—his flying is even described as driving—not only helps to authenticate the images of horror he brings back—an ambulance driver is more likely to see such atrocities than a pilot flying overhead—but also to make Wild more representative of American involvement in the war.

Before America entered the war many college students, and other young men, volunteered as ambulance drivers for the French cause. Their motives for joining were varied—some for the adventure, some for a love of France (Hansen, 128-31)—but for whatever reason, American ambulance drivers garnered much media attention back home. At a time when American reporting on the war was spotty and inaccurate the ambulance drivers were regarded as invaluable eyewitnesses. Many of them wrote letters home to local newspapers; some had their personal letters and diaries published in newspapers, magazines and books; and some, who were already professional writers, wrote articles for major metropolitan newspapers (Hansen, 85-7). By representing Wild as an ambulance driver the poem capitalizes on this reputation of the driver as an insider to European violence; one who brings authentic tales of the war from the front back to the American reader.

Paradoxically many American ambulance drivers were pacifists, like Harvard novelist John Dos Passos and his classmate Robert Hillyer. But they successfully negotiated their pacifism and their desire to save France from German aggression by volunteering as non-combatants (Hansen 151-2). In the poem, however, Horace Wild never admits to being a pacifist; his statement, "I don’t care who the hell calls me a pacifist," is far from an admission like "I am proud to be called a pacifist." This statement indicates that the term carries a negative connotation; and that although Wild may not necessarily apply the term to himself, he will not argue if others do. Wild’s anti-war argument tends toward a visceral reaction to the extreme and unnatural physical mutilation of bodies rather than take a philosophical or moral stance against violence and warfare. The poem certainly assures us that he is not averse to violence: "Horace Wild, the demon driver who loves fighting and can whip his weight in wildcats . . .."

In fact the poem goes out of its way to ensure that the reader does not confuse Wild for a coward; more than that, the poem emphasizes the masculinity of not only Wild but of the whole environment of the poem. The homosocial setting is unmistakable, three male friends sharing a meal "at a downtown club," and at least two are the epitome of machismo; Horace B. Wild, who, as one of America’s first aviators, survived his share of near fatal crashes in the days when flying airplanes frequently led to crashing airplanes; and Charley Cutler, who was not only a "famous rassler," but also the 1914 National Wrestling Alliance (the earliest professional wrestling organization) champion. The odd man out is Sandburg, a poet; however by slipping in the statement "now out of jail," the poem represents even him as rough, ready and not afraid to go in harm’s way.

This, perhaps conscious, need to assert the friends’ masculinity seems to indicate that masculinity is threatened in the space of the poem. The source of this threat comes not only from the possible labels of coward or pacifist, but from the particular form that violence takes in the poem. The second violent image, "the genital organ of the victim amputated and placed between the lips of the dead man’s mouth," because of its threat of castration, particularly stands out from the other three images. However, although the threat of castration is probably enough to provoke Wild’s anti-war response, something else is particularly troubling about the image; despite the gruesome detail, it is erotically charged. Although all the images are noticeably unadorned by descriptive qualifiers—allowing the images to plainly speak their horror—the word-choice for this particular image is odd. First, the word "placed" is much more gentle than other possible verbs, such as "shoved," "forced," or "crammed." The verb bespeaks of a lack of force or violence; if the image were to contain a descriptor, one can imagine more readily the adverb, "gently" than others such as "rudely" or "roughly." Second, "lips" itself is erotically charged, both through its sound and through what it signifies: the primary non-genital sexual organ in human beings. Sandburg could have omitted this detail—saying instead "placed inside the dead man’s mouth," or even "shoved into the dead man’s mouth"—without affecting the brutality of the image.

I give so much attention to this line because I think its erotic charge complicates an otherwise straightforward anti-war message. For Wild, Sandburg and the reader to be attracted to such a repellant image is troubling, to say the least. Furthermore, the poem heightens the homoerotic tension in the following line, "And Horace Wild, eating whitefish, looked us straight in the eyes." Wild’s masticatory act not only symbolizes communion—in response to the Christ-like Canadian soldier of line five—but also repeats the indignity of the second victim. The whitefish stands in for both the flesh of the first victim and the castrated genitals of the second; symbolically, Wild fellates both victims. We can read Wild’s response to the represented violence as not only a reaction to inhuman mutilation, and a fear of castration, but also as a fear of his own homosexual attraction to the bodies of the dead soldiers—a homophobic response. Therefore, the cause and effect logic of the poem—"because of these instances of violence I am anti-war"—contains a further element: "because I am attracted to these images of violence, I find war reprehensible." Wild is horrified by his compulsion to symbolically (and perhaps literally) repeat those violent acts. Pacifism, a term often associated with women and intellectuals, paradoxically becomes a site where Wild can maintain his masculine self-image in the face of the horrifically homoerotic violence of the European war.

Works cited

Bryce, the Right Hon. Viscount, et. al. Report of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages Appointed by His Britannic Majesty’s Government. 15 December 1914. 26 April 2001 <http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/brycere.htm>

Hansen, Arlen J. Gentlemen Volunteers: The Story of the American Ambulance Drivers in the Great War, August 1914-September 1918. New York: Arcade Publishing, 1996.

Copyright ? 2001 by Jeff Sychterz

------------------------------

AND THEY OBEY

SMASH down the cities.Knock the walls to pieces.Break the factories and cathedrals, warehouses and homesInto loose piles of stone and lumber and black burnt wood: You are the soldiers and we command you.

Build up the cities.Set up the walls again.Put together once more the factories and cathedrals, warehouses and homesInto buildings for life and labor: You are workmen and citizens all: We command you.

Sandburg is pulled in different directions on the topic of war, and that in itself is instructive. On one side, there is disgust and recognition that it is in the interests of ruling powers. On the other side, there is the feeling that there is no other way and resignation to inevitability. It's the "no other way" part that needs the most critical scrutiny.

2 Comments:

"Thanks for the comment.

I suspect there is more to it, too.

For too many centuries the Islamic sciences have been in the hands of kings and other powers more interested in using popular beliefs to prop up their own authority. Events like Shirazi's tabacco rebellion were much more the exception than the rule. Scholars found a safer way to respect by parading esoteric knowledge than by emphasizing the message of peace and justice. In the modern period, conflict itself has become a sort of cottage industry. Posturing and taking a hard line win more popular approval than trying to organize effective collective action. But maybe I'm missing something. I'm open to suggestions."

Salaam Dr.Legenhausen,

I had read a book titled "The Politics of Knowledge in Premodern Islam" by Omid Safi. The thesis of the book states that the Seljuk Turks effectively used the Ulema and the Sufis to legitimate their rule as supreme and from God. The turks in Iran would fund khanaqahs for sufis and would flower people like al-Ghazali with support and money if they helped in propagating the rule of the seljuks.

Omid Safi tends to praise Aynal Qudat, a sufi who was killed when speaking out against the Seljuk Authority. Aynal Qudats poetry is not only that which reflects the esoteric and the concentration with the absolute but also that off standing out for the truth and speaking out against falsehood, reminiscent of Imam Hussain (as)

wa'llahu alam

Thanks. I must get Omid Safi's book! I've heard a few interesting tidbits about Ayn al-Qudat, but haven't read anything in depth about him. Thanks also for reading and making comments. I put together this blog just as a place for my own notes about peace and understanding in Islam and other points of view, and I didn't really expect anyone else to be interested. Anyway, I appreciate your input.

fi aman Allah

Post a Comment

<< Home